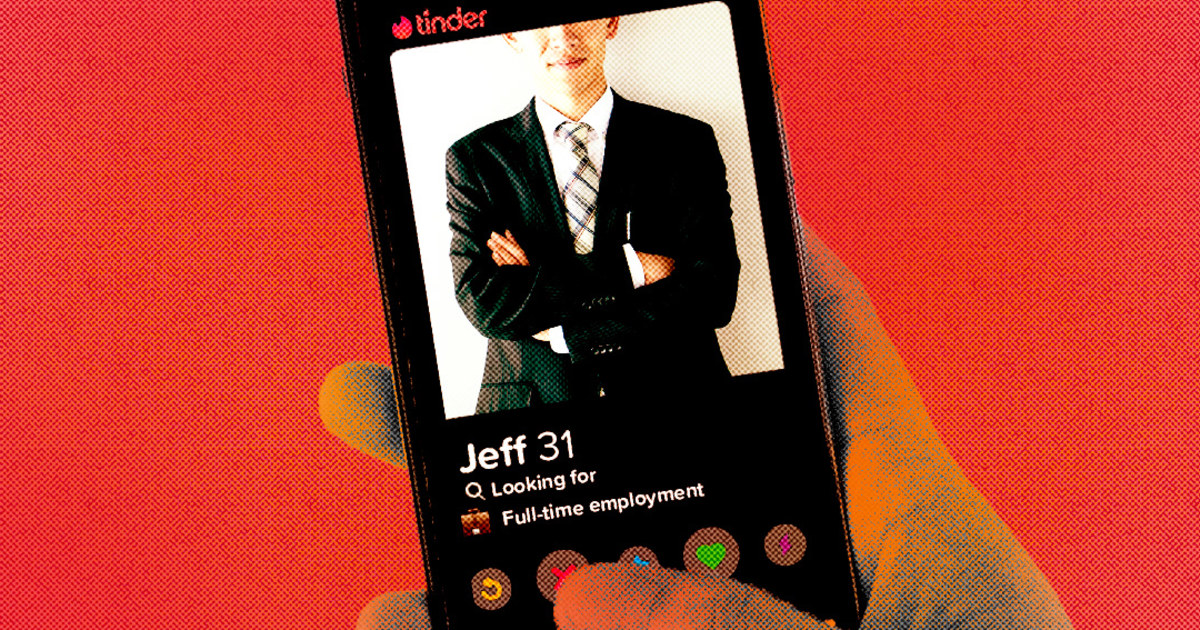

HONG KONG — Young people in China facing an increasingly tough labor market are turning to an unlikely place for help in their job searches: Tinder.

Jade Liang, a master’s student in Shanghai, decided to dust off her account on the dating app after applying to more than 400 jobs online without success. She had previously used it in her search for romance, but now finds it useful to connect with fellow professionals for casual coffee chats.

“I simply swiped right on individuals in the industry I aspire to join,” which is tech, said Liang, 26, who told NBC News that she makes her intentions clear once she starts chatting with matches online and that she finds the response is generally welcoming.

Liang is among job seekers in China who are resorting to unconventional methods because of fierce competition and a scarcity of job opportunities. Some jobless adults are even working as “full-time children” for their parents, doing chores and running errands in exchange for financial support.

China, the world’s second-largest economy after the United States, is struggling with youth unemployment, which hit a record 21.3% last June. After suspending the release of youth unemployment data for several months to revise the method of calculation, Chinese officials said in December that the jobless rate for people ages 16 to 24, excluding students, stood at 14.9%.

That compares with 8% unemployment among Americans ages 15 to 24 in the same month, according to the Federal Reserve.

Though high youth unemployment is not unusual for countries such as China that are also facing other economic challenges, “China’s problems appear to be more serious this time around,” said Su Yue, principal economist at The Economist Intelligence Unit in Shanghai.

“The country’s economic downturn, the impact of the pandemic, and the consolidation of industry all came at the same time, making the impact on the youth population even greater,” she said.

In the face of such pressures, “we can’t help but feel a surge of excitement when we come across someone working in the same industry, even while browsing a dating app,” said Joy Geng, a recent graduate of a British university who is now based in Beijing.

Liang first thought of Tinder as a job-hunting tool after she saw a viral post on Xiaohongshu, China’s equivalent of Instagram, by a user who said she had successfully found a job by using a Chinese dating app.

Similar posts suggesting dating apps as a way to find jobs are not uncommon on Chinese social media.

“When hiring managers ask me how I know the vacancy — me: Tinder,” read one widely shared meme last year.

Though Tinder is one of many foreign apps that are blocked in mainland China, residents can access it using virtual private networks.

“By using dating apps, we can reach more people,” Liang said. “Normally, we need a long period of time to get close to people. But with dating apps, you hang out with strangers for a couple of hours and they can already provide you with tons of their personal information.”

Geng said job seekers may also be turning to Tinder because they no longer have access to LinkedIn, which is also blocked in China after it announced it was pulling out of the country in 2021, and are dissatisfied with the domestic alternatives.

Liang said that even though she can access LinkedIn by using a VPN, she still tried Tinder because she found traditional job-hunting methods had failed her.

“The market is too saturated because of the economic downturn,” she said.

Tinder itself discourages the practice, saying its platform is designed to foster personal relationships, not business ones.

“Tinder is not a place to promote businesses to try making money,” a company spokesperson told NBC News in a statement.

It has also drawn criticism from those genuinely seeking romantic connections who say they can no longer trust other users’ motivations.

“I cannot believe people would even go on dating apps to find jobs,” read one comment on Weibo, China’s equivalent of X. “I cannot believe a word a dating app user says in the introduction.”

Romy Liu, who previously worked for an executive search company in the Chinese city of Hangzhou, said that from an employer’s perspective, finding a job opportunity through Tinder would suggest that an applicant has “strong social skills” and made a strong enough impression on someone they just met to get a referral.

“I would think that someone who can get a job through this kind of platform is awesome,” she said.

But it’s less efficient compared with traditional job-hunting methods, she said, and “may only be viable when seeking employment with international companies or internet giants.”

And not all employers might look so kindly on the Tinder approach, Liu cautioned.

“If a state-owned company has ever heard of you hunting for a job on Tinder, I think they might permanently blacklist you,” she said.

Zoey Zeng, who works in the finance industry in Paris, said that while the Tinder method is available to job seekers worldwide, some factors might make it more effective in China, where it is used mainly by highly educated professionals.

Tinder users in China “are already very selective because the vast majority of users were pursuing degrees overseas,” Zeng said. “But in France, Tinder is known for finding sexual partners — 90% of people I got in touch with wanted to find friends with benefits.”

“I think the purpose of this kind of software in China and abroad is still not the same,” said Zeng, who uses Tinder only for networking.

She said she still found Tinder a useful professional tool in Paris as “even if it is not very efficient from my end, I am still able to network with people that match my background precisely.”

Liang is still looking for opportunities in China.

“I’m kind of tempted to give up because it’s just so hard to find an ideal job,” she said. “But I believe I’ll get substantial help if I actively use dating apps or more ways for job hunting.”