BINTULU, Malaysia — In the open sea off the coast of Malaysian Borneo, industrial rigs extract massive amounts of oil and gas that fuel the economy of Malaysia.

But Malaysia is running out of oil and gas close to shore. Increasingly, it has to venture farther out to sea, raising the likelihood of direct confrontation with Chinese forces in the South China Sea.

As tensions rise throughout the South China Sea, one of the world’s busiest and most contested bodies of water, energy demands are drawing Malaysia deeper into the fray and testing the country’s long-standing reluctance to antagonize China, according to interviews with more than two dozen government officials, diplomats, oil and gas executives and analysts in Malaysia.

Some of Asia’s biggest oil and gas reserves lie under the seabed of these disputed waters, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Since 2021, Malaysia’s state-owned energy company, Petronas, has awarded several dozen new permits for companies like Shell and TotalEnergies to explore new deposits here, many in so-called “deepwater” clusters more than 100 nautical miles from shore but still within the boundaries of what Malaysia considers its exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

These developments are teeing up more confrontations with China, warn energy and security analysts. Already, federal and provincial officials in Malaysia have been beefing up military deployments around the industrial port town of Bintulu in the state of Sarawak, where much of the country’s oil and gas industry is based, and Malaysia has been increasing military cooperation with the United States, particularly on maritime security. For the first time later this year, a bilateral army exercise that Malaysia conducts annually with the United States will be held on Borneo, said a U.S. State Department official.

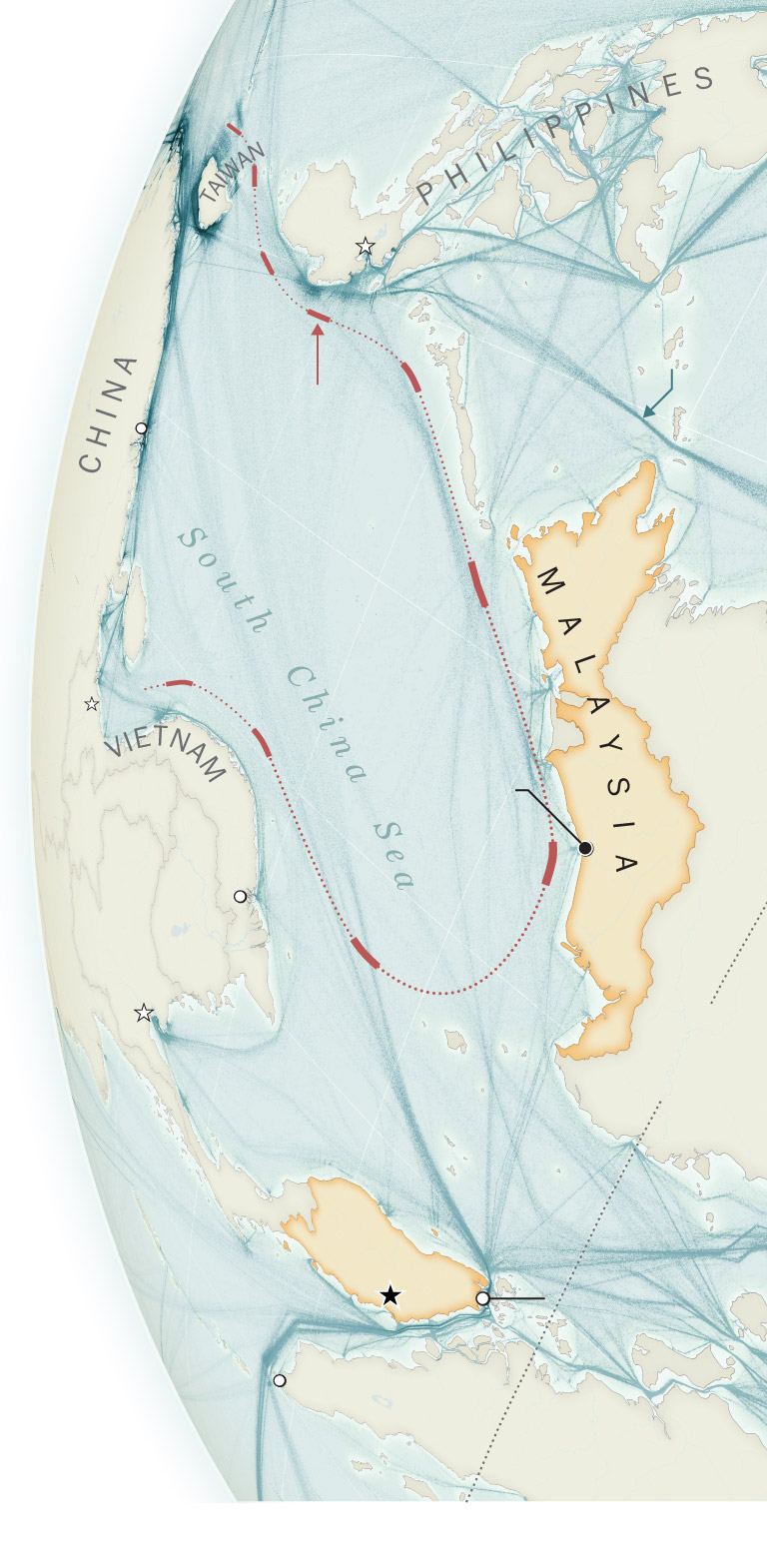

China’s

maritime

claims

Shipping routes

source: World Bank

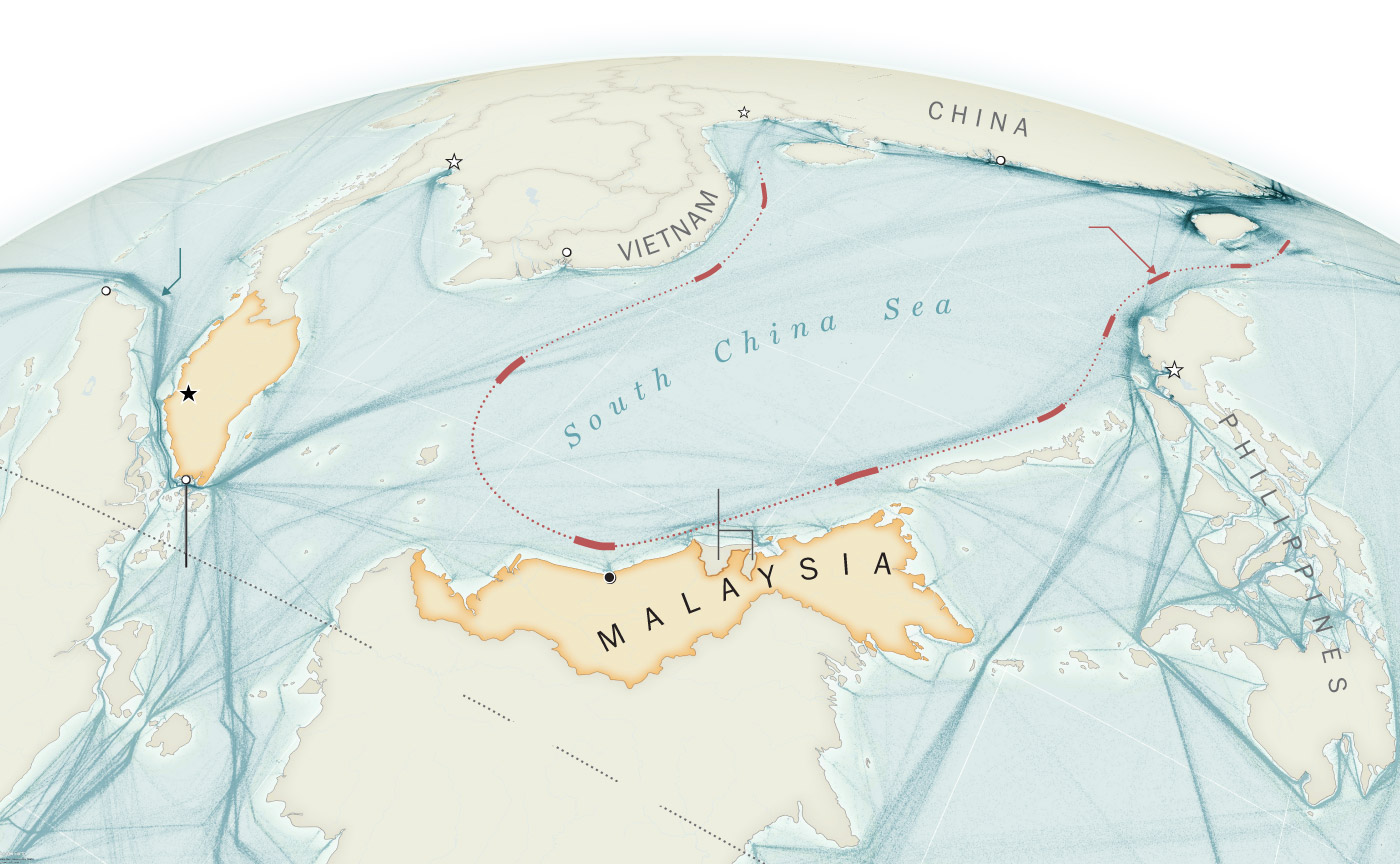

China’s

maritime

claims

Shipping routes

source: World Bank

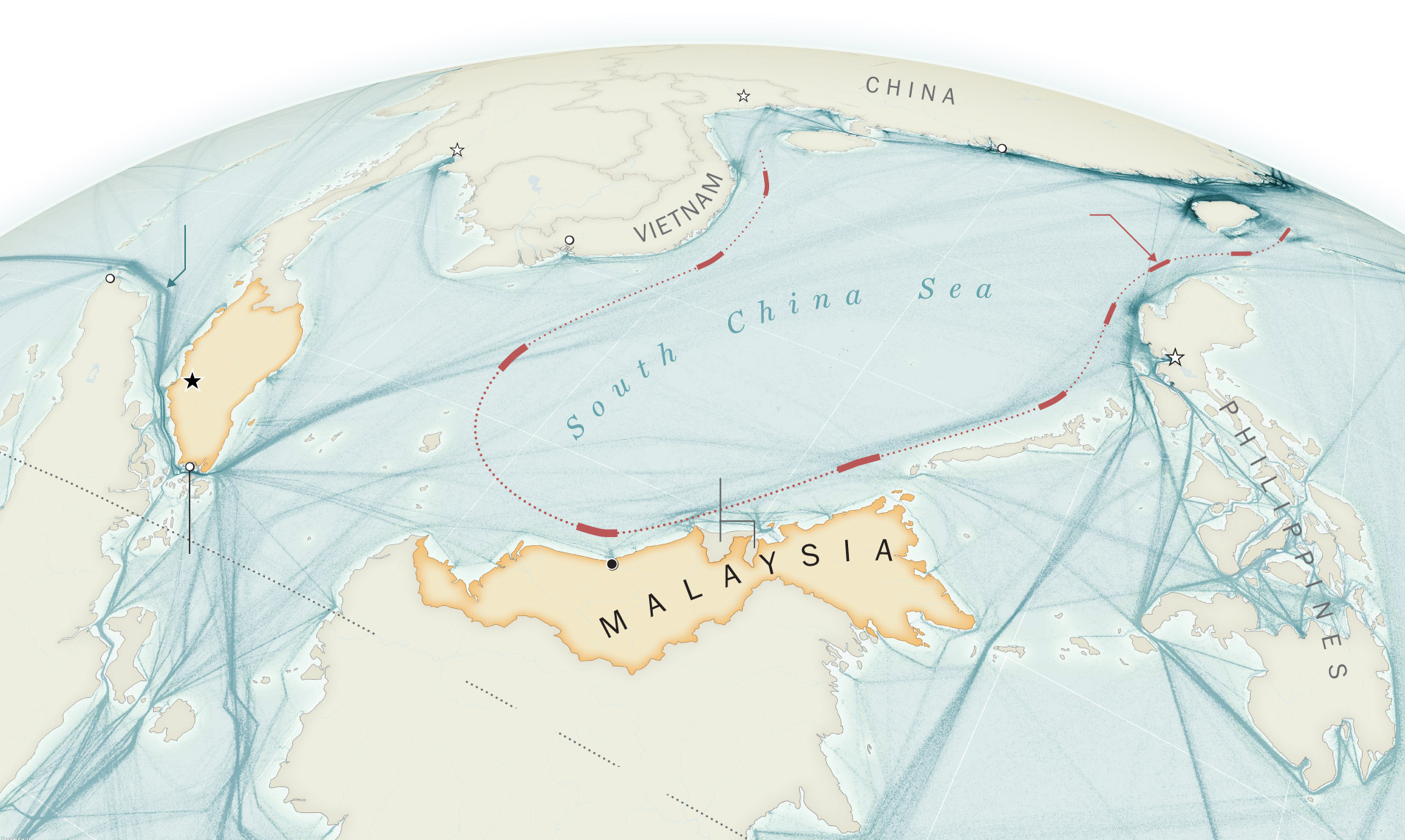

China’s maritime claims

Shipping routes

source: World Bank

China’s maritime

claims

Shipping routes

source: World Bank

At least since 2020, China has been harassing Malaysian drilling rigs and survey vessels, leading to standoffs that have lasted months, according to satellite imagery and data that track ship movements. For years, Malaysia’s response has been muted — a calculation shaped by reliance on Chinese investment and the relative weakness of the Malaysian military, said Malaysian security analysts and defense officials. Unlike the Philippines or Vietnam, Malaysia rarely publicizes Chinese intrusions into its EEZ, which extends 200 nautical miles off the coast, and withholds how often these incidents occur from journalists and academics.

In an exclusive interview, the director general of Malaysia’s National Security Council dismissed concerns of Chinese harassment even as he acknowledged that Chinese vessels had been patrolling Malaysian waters nearly nonstop.

“Obviously, we prefer for Chinese assets not to be in our waters,” said Nushirwan bin Zainal Abidin, who was ambassador to China from 2019 to 2023. But there’s no need, he added, for the dispute to “color” Malaysia’s broader relationship with its largest trading partner. “We can let sleeping dogs lie,” Nurshirwan said.

Despite objections from countries in Southeast Asia, China has laid claim to almost the entire South China Sea, building artificial islands and deploying vessels to enforce what it calls the “10-dash line,” delimiting on maps the boundaries of what China says are its waters, which come within 30 nautical miles of the Malaysian coast.

While much attention in recent months has been paid to China’s intensifying encounters in contested waters with Filipino fishermen and coast guard, tensions stirring farther south, where the world’s biggest oil and gas companies have deeper interests, have gained far less notice. Asked about Malaysia’s claims of Chinese incursions, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs said in a statement that Chinese vessels have been conducting “normal navigation and patrol activities” in areas under its jurisdiction.

Malaysia has for decades sought to “decouple” the South China Sea dispute from trade and investment with China, said a high-ranking Malaysian official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he had not been authorized to address the issue.

But the country’s need for offshore oil and gas is starting to upset this delicate balancing act, the official said. He noted that Chinese coast guard vessels have repeatedly disrupted operations at the Kasawari gas field, which contains an estimated 3 trillion cubic feet of gas and where Malaysia has recently built its biggest offshore platform. “For what’s happening at Kasawari, I don’t have a solution,” the official said. “Right now, no one does.”

Venturing into deeper waters

In the 1970s, before Shell discovered large deposits of oil and gas off the coast, Bintulu was a small fishing village with a single stretch of road connecting a mosque to a market. Today, it’s a throbbing hub of industry, anchored by a 682-acre processing facility that produces 30 million tons of liquefied natural gas per year. In 2023, Malaysia was the world’s fifth-largest exporter of LNG, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Malaysia has relied on these resources to drive growth for decades, deriving 20 percent of its gross domestic product from oil and gas. But several years ago, industry analysts warned that the country’s era of “easy exploration” was ending. Oil and gas found in shallow waters, meaning at depths less than 1,000 feet, were running out. Companies knew there were more deposits remaining, said San Naing, a senior oil and gas analyst at BMI, a market research firm. “They just had to go farther out.”

Nearly 60 percent of Malaysia’s gas reserves are located off the state of Sarawak, says the country’s energy regulator. Starting in 2020, Petronas ramped up exploration. Two years later, having reported a string of new discoveries, the company awarded 12 new licensing contracts to energy conglomerates looking to operate in Malaysia, the most since 2009.

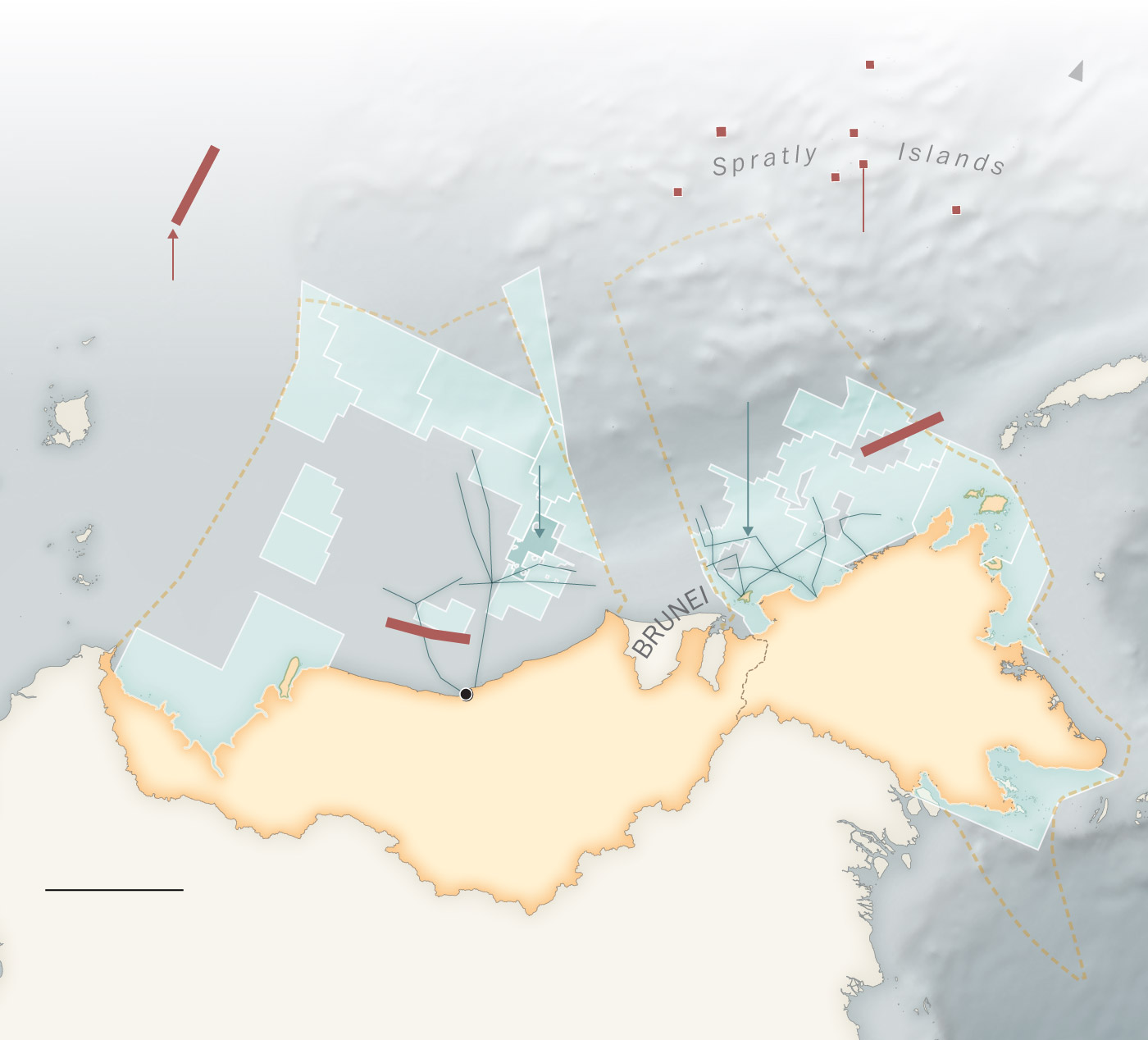

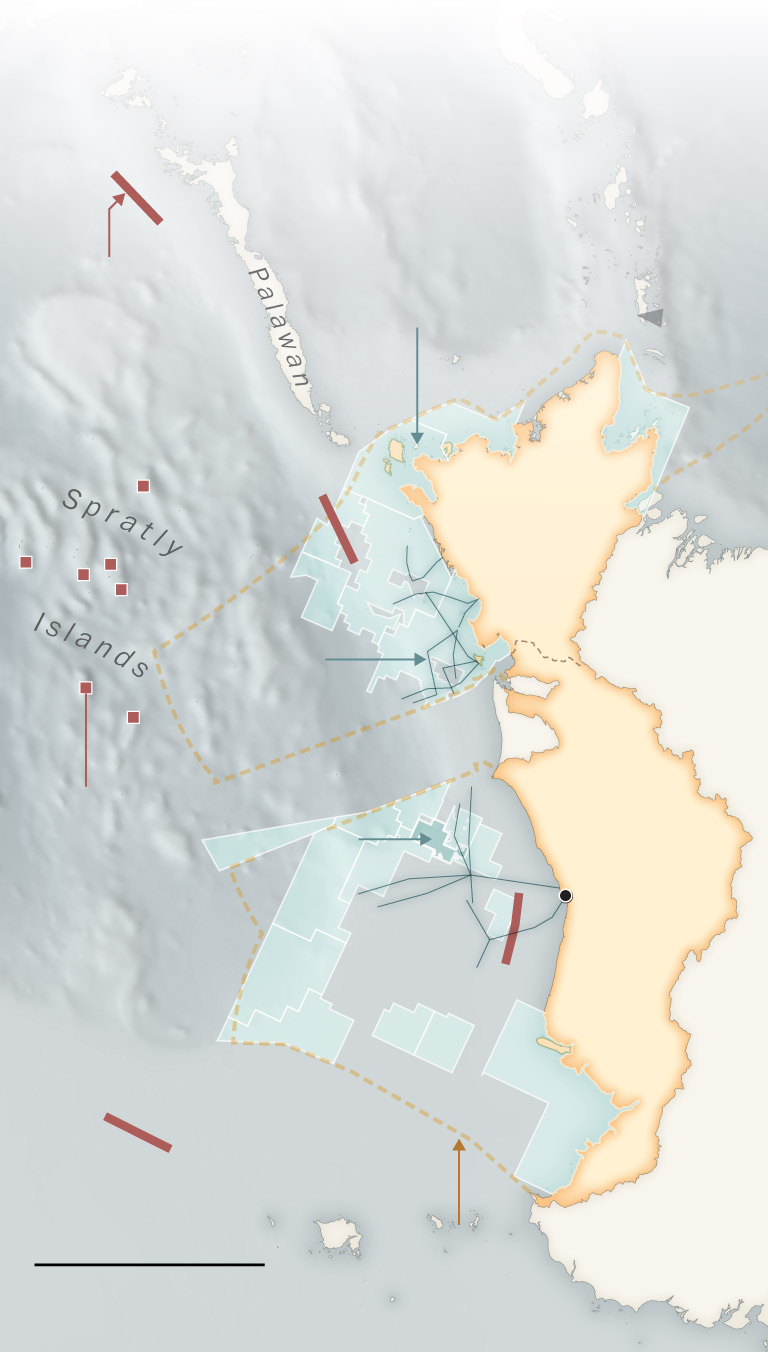

Malaysia has harnessed offshore oil and gas for decades but began markedly increasing

exploration in waters further offshore starting in 2021.

Seven islands occupied

by China in the Spratly

Island chain.

China’s maritime

claims

Existing

oil and gas

pipelines

Oil and gas blocks

licensed for exploration

by Malaysia in the

last three years

Source: Petronas and MarineRegions.org

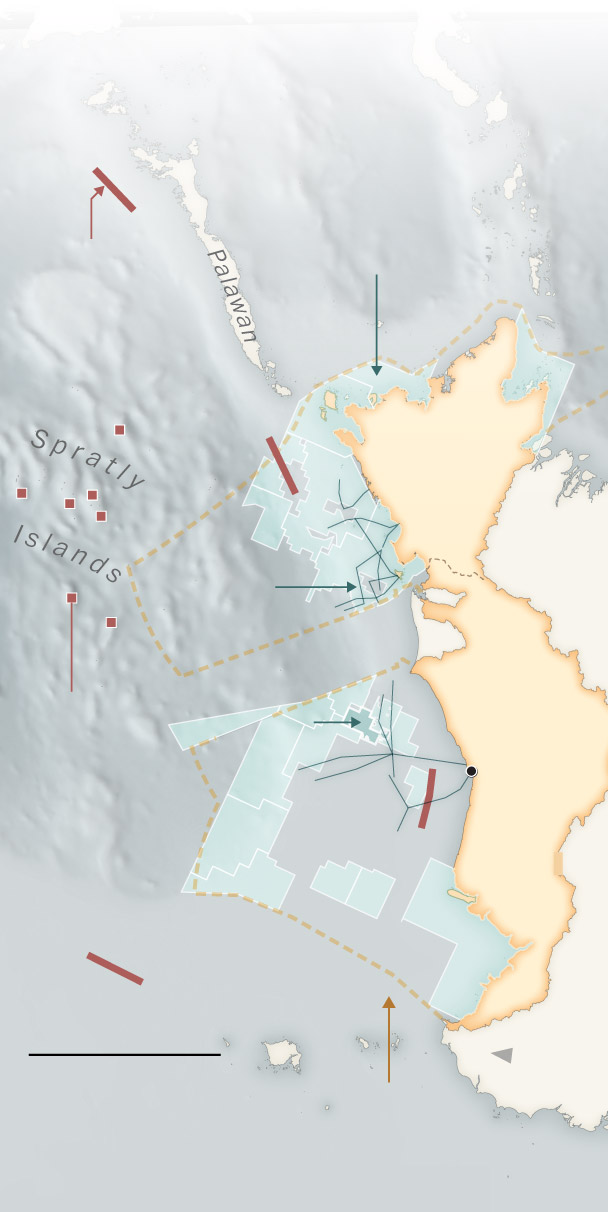

Malaysia has harnessed offshore oil and gas for

decades but began markedly increasing exploration

in waters further offshore starting in 2021.

Oil and gas blocks

licensed for exploration

by Malaysia in the

last three years

China’s

maritime

claims

Existing

oil and gas

pipelines

Seven

islands

occupied

by China

within the

Spratly

Island

chain

Malaysia Exclusive Economic

Zone (EEZ) boundary

Source: Petronas and MarineRegions.org

Malaysia has harnessed offshore oil and gas

for decades but began markedly increasing

exploration in waters further offshore since

starting in 2021.

Oil and gas blocks

licensed for exploration

by Malaysia in the

last three years

China’s

maritime

claims

Existing

oil and gas

pipelines

Seven

islands

occupied

by China

within the

Spratly

Island

chain

Malaysia Exclusive Economic

Zone (EEZ) boundary

Source: Petronas and MarineRegions.org

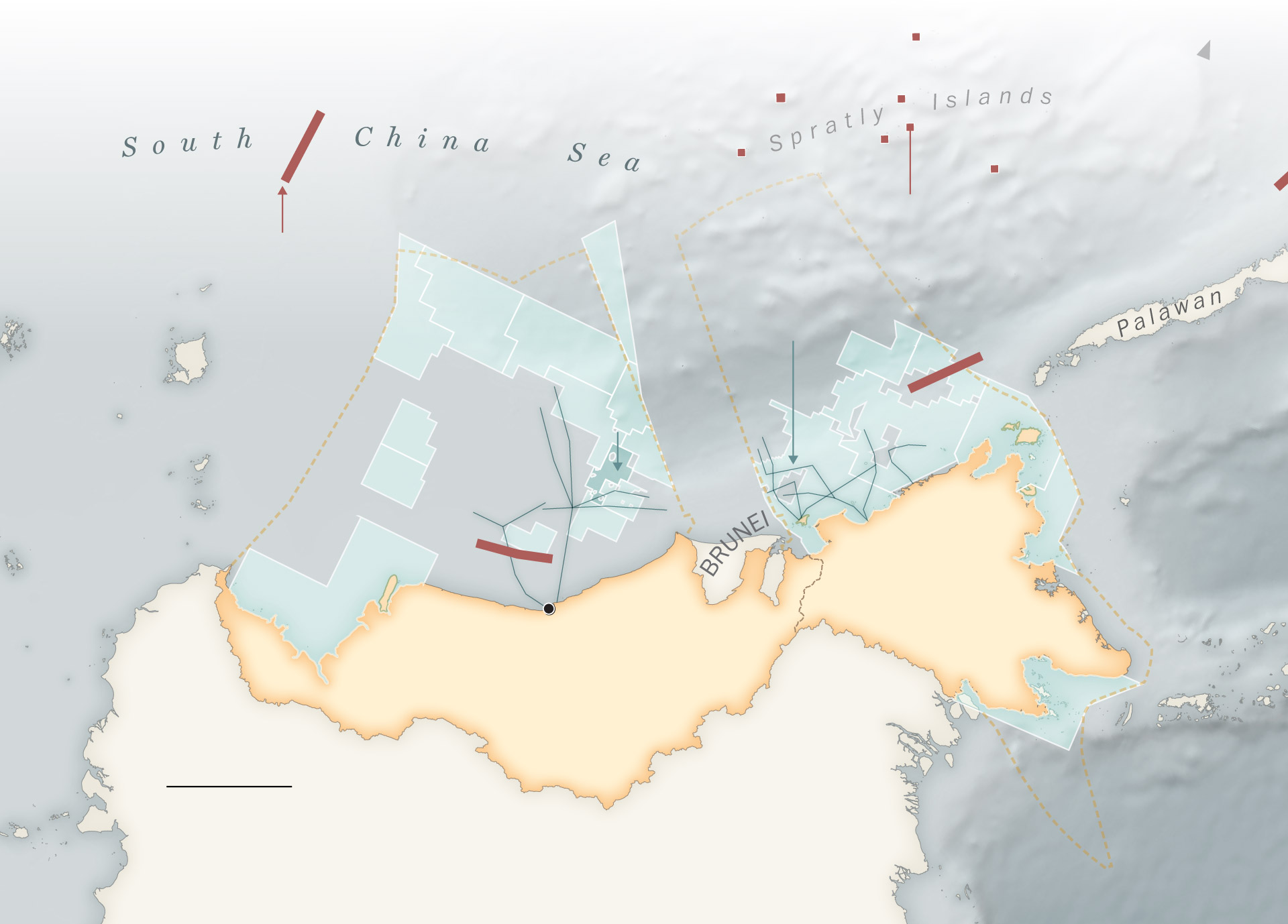

Malaysia has harnessed offshore oil and gas for decades but began markedly

increasing exploration in waters further offshore starting in 2021.

Seven islands occupied by China

within the Spratly Island chain

China’s maritime

claims

Existing

oil and gas

pipelines

Oil and gas blocks

licensed for exploration

by Malaysia in the

last three years

Malaysia’s

Exclusive Economic

Zone (EEZ) boundary

Source: Petronas and MarineRegions.org

Petronas executives say this enthusiasm is a sign of “investor confidence.” But in private, investors have been fretting over the risks of operating in the South China Sea, said a veteran oil and gas analyst who researches Malaysia and who spoke on the condition of anonymity to protect business interests. “What happens when the Chinese boats turn up? That’s always front of mind,” said the analyst.

In 2018, after harassment by Chinese vessels, Vietnam called off a major oil project midway through construction, leaving the companies involved with an estimated $200 million in losses. That incident was a “shock to the industry” and drove companies to reconsider investments in the South China Sea, said the analyst. Malaysia’s new discoveries are encouraging companies to return. But the risks now are arguably higher than ever.

A handful of Chinese vessels patrol the waters at Luconia Shoals, about 60 nautical miles off the Malaysian coast, near major gas fields like Kasawari. But a much bigger fleet of hundreds of Chinese coast guard ships and maritime militia are based farther north, near the Spratly Islands, where Petronas has designated new clusters for oil and gas exploration. The closer Malaysia’s energy projects come to the Spratlys, the greater the likelihood of confronting the Chinese, said Harrison Prétat, deputy director at the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at D.C.-based Center for Strategic and International Studies.

In recent months, Chinese officials have said pointedly that the exploration of resources in the South China Sea “should not undermine China’s territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests.”

Petronas rejected requests for interviews and did not respond to inquiries about the South China Sea. But last year, after Beijing released a new map of the waterway that expanded Chinese claims, Petronas’ chief executive, Tengku Muhammad Taufik Aziz, made an unusually strong statement of objection. Extracting offshore oil and gas is within Malaysia’s sovereign rights, he said. “Petronas,” he added, “will very vigorously defend Malaysia’s rights.”

The U.S. government has rejected China’s expansive claims in the South China Sea but has not formally endorsed Malaysia’s claims.

A ‘fundamental rethinking’

Three years ago, a fleet of 16 Chinese military planes conducting an exercise over the South China Sea entered Malaysian airspace, said Malaysian officials. The incursion elicited rare rebuke from the Malaysian air force, which called it a threat to national security, and prompted the Malaysian minister of foreign affairs to summon the Chinese ambassador. Writing for a think tank, a trio of Malaysian scholars said the incident had “sparked fundamental rethinking within the Malaysian establishment about the country’s China policy.”

Chinese officials, however, denied that its planes had ever entered foreign airspace. A Chinese state-run think tank, the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, said military aircraft were free to fly over the airspace of the South China Sea since its boundaries were “unclear.”

By the end of 2021, Malaysia had announced that a new air base would be built near Bintulu. Soon after, an army regiment from a neighboring city was moved in and last year, defense officials said they had worked out a plan to establish a new naval base. Speaking in Parliament, Defense Minister Seri Mohamad Hasan said Malaysia’s oil and gas would be protected “at any cost.”

Since 2021, Malaysia has also been increasing defense spending and strengthening military cooperation with the United States. Malaysia has received drones, communication equipment and surveillance programs, including long-range radar systems, installed on Borneo, to “monitor the sovereignty of airspace over the coastlines,” officials say. Later this year, Malaysia is set to get a decommissioned U.S. Coast Guard cutter and hold the annual bilateral army exercises with the U.S., called Keris Strike, on Borneo, according to the State Department official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to share private negotiations.

Little of this has been highlighted by Malaysia. It is eager to avoid becoming “entangled” in the geopolitical contest between the United States and China, said the high-ranking Malaysian official.

He said he presumes that China “sees” everything happening in the South China Sea. “The question is will they see what we’re doing and allow it.”

Christian Shepherd in Taipei, Taiwan and Desmond Davidson in Kuching, Malaysia contributed to this report. Maps by Laris Karklis.