Illustration: Xia Qing/GT

Editor’s Note:Official interactions between the US and China have been on the rise recently. According to the State Department, US Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Daniel Kritenbrink will travel to China from Sunday to Tuesday, following the phone call between Chinese and US leaders early this month and US Secretary of Treasury Janet Yellen’s China visit last week. Global Times (GT) reporter Wang Wenwen interviewed Ben Harburg (Harburg), a managing partner of MSA Capital, a venture capital firm. He is also a member of the Board of Directors of the National Committee on US-China Relations. He talked about the bilateral relationship from a US businessman’s perspective.

GT: How would you analyze these recent communications between the two countries?

Harburg: The scariest thing was when we were not talking, because when you’re not talking, there are no hotlines to pick up if something happens like two boats or planes collide over the South China Sea. That’s when the worst-case scenario can happen.

I think the resumption of communications is critical. The tone has been relatively constructive. The tone of US Secretary of Treasury Janet Yellen’s meetings has been positive. She talked about challenges around dumping and other things, but also a path to finding ways to solve them. She also acknowledged that we cannot decouple and our two economies are deeply integrated.

Our organization [the National Committee on US-China Relations] helped to arrange the meeting with President Xi. Many of the people in that room are people who are doing a lot of business with China and are constructive in engagement. Those that are on the fence or the more hawkish side are the ones that need to be engaged and brought back to the table. I would encourage China to bring in more global students and journalists.

Overall, the communication line opening is the first and most basic step to avoiding outright confrontation.

GT: MSA Capital has invested a lot in Chinese technology companies. How do you see China’s technology development?

Harburg: Now, we’re in a different era with the development of Chinese technology. When we first started investing in China, we were in Generation 2.0, mainly the consumer-facing mobile-facing technologies. China now is evolving to what we call Generation 3.0 focusing on AI and core technology opportunities, which is natural, because China has to become more efficient and more evolved as a technology ecosystem. Chinese technology companies that are building products that address global markets, particularly cross-border e-commerce and hardware, are also areas where we invest.

China is still the largest consumption market in the world and is still early in its development. The American technology ecosystem has a 40 or 50-year head start. China is really only in its second decade or so in terms of its technological evolution. So that means that there are huge opportunities to penetrate in efficiencies in local manufacturing and urbanization, with the consumers coming from rural areas to first-tier or second-tier cities, as well as investing in all those ways China is building its own self-sufficiency. Obviously, a lot of the decoupling exercise and deglobalization has resulted in China needing to build its own equivalent businesses for global markets.

Ben Harburg Photo: Wang Wenwen/GT

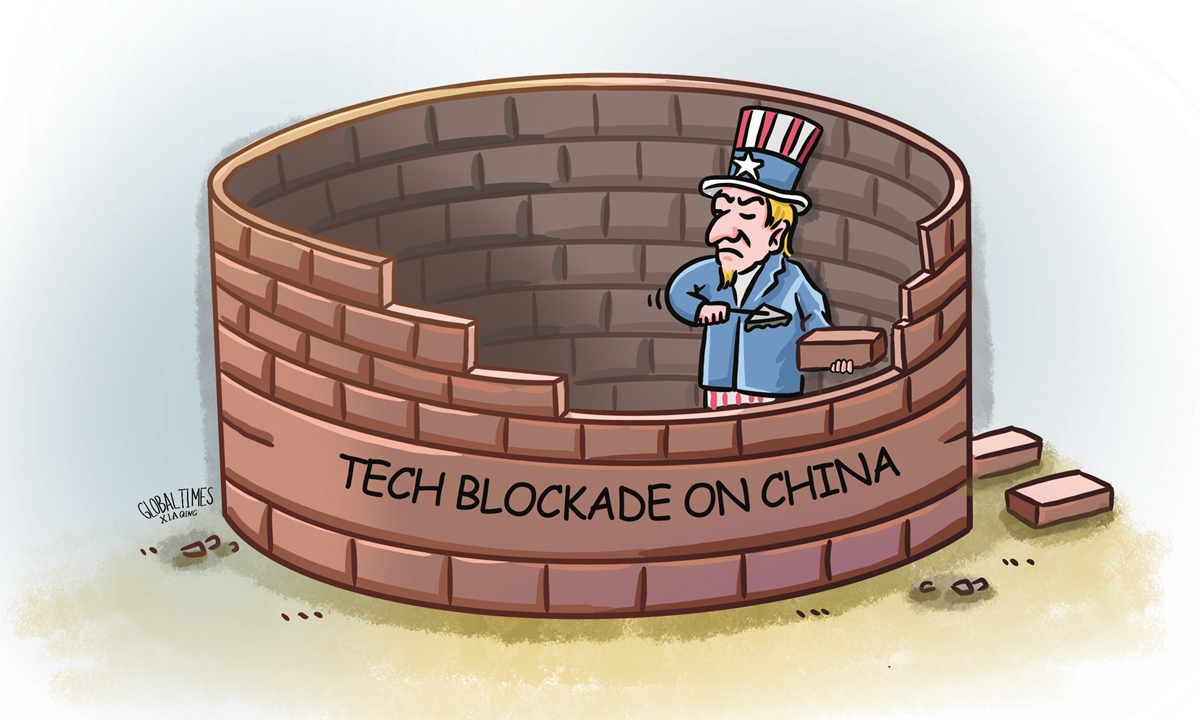

GT: China and the US are locked in a tech race. We have seen US tech blockade on China. Do you think such a policy is self-defeating?

Harburg: Naturally, when you’re an incumbent leader, you want to protect your advantage. It makes sense from a competitive dynamics perspective that the American government and companies do everything they can to curtail China’s ability to challenge those businesses. Back in 2018, the American banning of core components going into ZTE and Huawei illuminated to China the vulnerabilities that it had in its technology and supply chain infrastructure. This threw China into overdrive to find ways to wean itself off dependence on American key inputs.

In the short term, that will hurt China. In the early days, the likes of Huawei and ZTE were saying this would be hugely detrimental to their business. But in the long term, China will be entirely self-sufficient and independent of any American inputs.

In essence, the US made its chief competitor and economic rival aware of its weaknesses and the areas in which the US could hurt them the most. The US also pushed China to self-sufficiency and then, through a whole slew of unforced errors, undermined our own kind of gene pool and our own technological leadership by making it less friendly for global students, particularly Chinese students, to study in America. The net result is that we’ve weakened our long-term competitiveness for short-term gains by blocking China’s immediate economic and technological ascendance.

My No.1 recommendation to the American government has always been, rather than being fixated on putting up walls to the Chinese, focus on putting your foot on the gas and driving forward American innovation.

GT: You believe that in the next few decades, China will outcompete the West in some areas. Amid the current challenges to China’s economy, are you confident about the sustainability and tenacity of China’s economy?

Harburg: I’m definitely long-term bullish on China’s economy. It’s just inevitable to me that a country of this scale, with its own brand of capitalism with Chinese characteristics, can still thrive. So I don’t think that there are huge challenges from an economic model perspective. And you have an incredibly hard-working population that’s chock-full of the smartest PhDs as well as STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) graduates globally.

China has done all this under such a compressed timeline. When people were critical of China for having a high degree of pollution in Beijing during my time here, you have to remember that China went through its whole industrial revolution in a period of just 20 years. In the West, if you went to major cities like London or Pittsburgh, it took 100 years to clear out that smog.

China has a lot of headwinds that are external, and it also has headwinds that are internal. As those challenges internally work out, then it’s more about how China places itself in the global competitive dynamic to ensure continued growth.

GT: In last year’s Foreign Policy article, you argued that America can’t stop China’s rise and it should stop trying. Today, do policy elites in Washington have the same view?

Harburg: We tried to walk through on a historical basis and very binary, objective terms other times that different countries tried and failed to stop China’s access to other technologies such as satellites, and nuclear technology. Then we went with the argument that I mentioned earlier that fixating on illuminating China’s vulnerabilities by asking other countries to try to constrain China technologically by focusing more on throwing up walls rather than putting our foot on the gas is actually undermining our own technological development.

We’ve told people in Washington the same. Are they getting the message? Unlikely, right now. Until America starts recognizing that they really are helping China to build self-sufficiency to build Chinese market leadership and core technology vertical where America was once the undisputed leader, I don’t think they will recognize the negative effects of their policies.

GT: From the perspective of a businessman, do you see the potential for the two countries to ease the relations in the future?

Harburg: There were some really low moments at the very tail end of the Trump administration. There was just this feeling that something could set off a hot war, even though we’re kind of in a quasi-cold war today. That was probably the lowest moment. We were edging a little bit upward. But I don’t expect huge progress as we’re in an election year. Both sides of the political aisle will compete for the title of who was tougher on China.

We are all trying to project what will happen over the next couple of years. If it’s another Biden administration, you can just expect more of the same kind of this detente, and certainly continued actions being taken by the American side against Chinese businesses such as restricting capital and technology flows into China. That has implications for us as businessmen because we understand that there will be less global capital available for China and fewer global markets for the Chinese to access. Certain technology verticals in China will be challenged in the short term because they won’t have access to American chips or other kinds of critical inputs.

If Trump wins, it’s a very binary situation. Expectations are already very low with his claim of a 60-percent tariff on China. However, we all know that Trump is a deal maker and he’s more transaction-oriented. So, ironically, if China comes to the table with a serious intent to do a deal with Trump that covers many of America’s grievances such as IP protection and trade imbalances, you could actually find a more binary outcome where US-China relations could improve significantly overnight. That again has ramifications for us in business. Maybe we will be in some significant short-term pain. But in the longer term, we could see things normalized.

But generally, I don’t expect there to be a recoupling or a reintegration of the economies. I think we’ll just get to a stasis. What we’re hoping for at this moment is to keep the lines of communication open, avoid a hot war and find some balance.