Gambling is considered taboo across Malaysia’s multicultural society – especially among the ethnic Malay majority, who are predominantly Muslim and legally barred from engaging in any form of betting. Yet Malaysians are also prolific gamblers, with the country’s nationals regularly appearing at gaming tables elsewhere in Asia.

Berjaya Corp, which owns Malaysia’s largest lottery business, was one of the parties Bloomberg said had held talks with Anwar.

The company’s lawyers have lodged a police report to find out the identity of the “unnamed source” in the report, whom they alleged spread “completely untrue and false statements”.

“We trust the police will do the necessary to investigate this matter, and respectfully encourage any publication to be done more tactfully before making any allegations without prior verification,” Berjaya Corp said in a statement issued late on Sunday.

A representative from Bloomberg’s public relations team in Asia said the outlet had no comment on the issue for now.

The contentious story, published on Thursday, cited unnamed sources who said Anwar had met Berjaya Corp founder Vincent Tan and Lim Kok Thay of Genting Group – which runs Malaysia’s sole casino complex – to discuss the possibility of setting up a new casino after the country’s first and only gambling licence was issued over 50 years ago.

Berjaya Corp and Genting later issued separate statements denying that their leaders were involved in any such talks.

Media freedom advocates have raised concerns about the potential impact on free speech and public discourse following the reaction to the Bloomberg report from Anwar and the companies that were named.

Anwar and the companies “should walk back their threats to the anonymous sources cited in the story and allow the press to report on issues of national import without fear of reprisal”, said Shawn Crispin, senior Southeast Asia representative of the US-based Committee to Protect Journalists.

“Anwar’s government was elected on a reformist platform but this type of intimidation of the press harkens darkly to Malaysia’s authoritarian past.”

“Obviously, if [Anwar] is involved in the casino thing, it will damage his reputation as an Islamist … It’s taboo for him politically, seeing as how he is trying to court the Muslim or right-wing vote,” said James Chin, a professor of Asian studies at the University of Tasmania.

“I suspect the sultan will not allow the casino to be there, unless they do a special deal like in Singapore where locals cannot visit,” Chin told This Week in Asia.

Broad public opposition to gambling, however, has not stopped companies from wading into the lucrative business, and making hefty tax payments to the government.

Since securing the country’s sole casino licence in 1969, the Genting Group has grown into a multibillion-dollar conglomerate that operates a sprawling casino business spanning Malaysia, Singapore, the Britain and the United States.

Genting reported gross revenue of about 10.2 billion ringgit (US$2.1 billion) in 2023 from its Malaysia operation, and paid the government some 313.3 million ringgit in taxes that year.

Berjaya Corp’s popular Sports Toto lottery brand was taxed around 106.1 million ringgit in the 2023 financial year, when it earned a little over 6 billion ringgit in revenue.

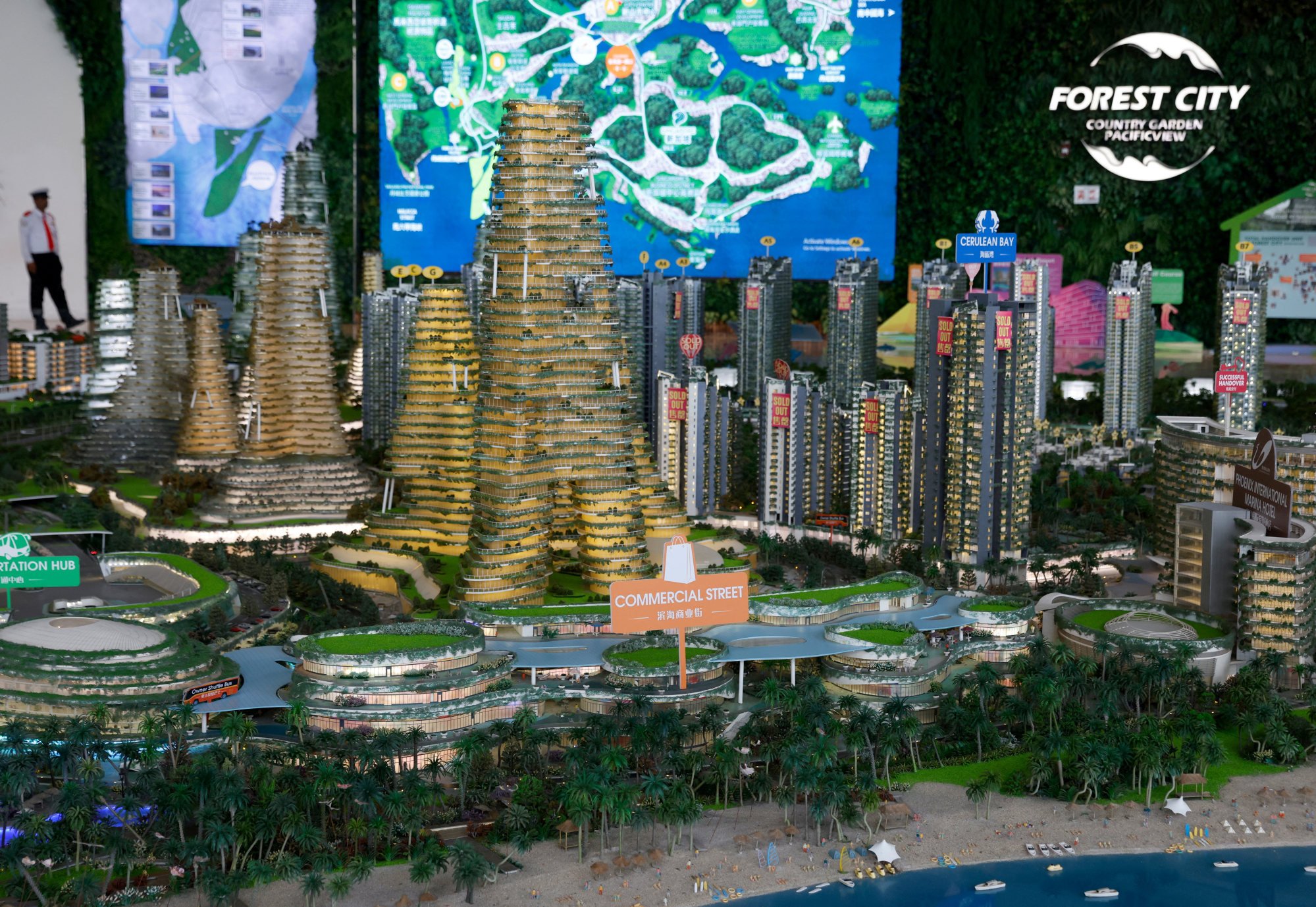

Forest City’s troubles deepened in 2020 after China’s government imposed capital controls to stabilise the yuan, which virtually cut off access for clients from developer Country Garden’s core target market.